The digitization of products

Michele Scian

Manager, content designer

Transformative innovation

2022

How design and 3D modeling can speed up and ease the product development process, especially in fashion.

The relationship between physical and digital is a constant in modern times, especially after the pandemic, among other things, has forced us to take a second look at it, with the latter becoming — predictably — more and more critical. Today, even objects that would be physical by definition don’t need to be made of matter. To sell a product, it is not mandatory that a tangible copy of it be made, that a prototype be constructed so as to evaluate its craft. Most of the time, a digital copy will do just fine. As a result, the dematerialization process we have seen take place in music is now spilling over to other sectors.

And 3D design is the kingmaker here. 3D technology has evolved enormously in both rendering quality and speed over the past decades; so much so that some virtual models are indistinguishable from reality at first glance. The evolution in image quality and level of detail has become apparent in the world of film, too.

A comparison between 1994’s original “Lion King” movie and its 2019 remake.

1968’s “Planet of the Apes” next to its 2001 remake.

We have gotten used to the level of quality 3D design allows for, and thanks to new, sophisticated software, this technology has become easier to use and thus more widespread in various fields. Fashion has been at the forefront of this adoption, so much so that many companies have entirely rethought their way of designing clothes, shoes, and accessories.

Prototypes: from physical to digital

Let’s use some examples. What does to dematerialize and then virtualize a product actually mean?

- Making decisions about a product’s final design before its physical creation. Sketching out an idea quickly, testing a few variants, and sharing them with several people without needing everyone to have the hard skills required to imagine the end result. This both cuts development times significantly and enhances collaboration.

It is often the case that multiple prototypes get made to evaluate how different materials look. Sometimes, however, tight development times make it possible to have just one physical version of the product, whereas 3D prototyping allows experimenting with several different solutions.

- Experimenting more, faster, and spending less time on making color and material variants, while also looking at all of a product’s SKUs.

It becomes possible to get a full picture of the color and material variants in just a few minutes, without ever developing a physical prototype.

- Coming up with marketing material quickly and consistently. A digital-first workflow allows us to create images, videos, technical sheets, and other kinds of output right from the get-go. This makes it possible to have a virtually endless repository of useful assets to draw from, and thus cut down the time between a collection’s introduction and the actual campaign.

3D modeling allows for the creation of entire photoshoots without ever snapping a picture. Here’s a secret: the black dress doesn’t actually exist, it has only been modeled as a 3D object!

- Testing and measuring a product’s level of satisfaction through digital channels like internal platforms or social networks. Buyers or clients can express their feelings and give feedback before a product enters production.

- Creating interactive experiences in AR/VR which allow to showcase a product without having to actually manufacture an asset.

Wanna allows developers to integrate AR technology within one’s website or mobile app, and lets users “try on” shoes digitally right on their feet. In this way, a product can be launched onto the market before a physical product is ever created.

- Reducing goods circulation between multiple locations. Digital objects don’t need to be moved at all, and often have sufficient details to be judged and tested.

- Cutting down on the environmental impact of production, as fewer materials are used to create prototypes. Experimentation with digital materials means that variants and prototypes can be cut down significantly, getting to production only after several validations.

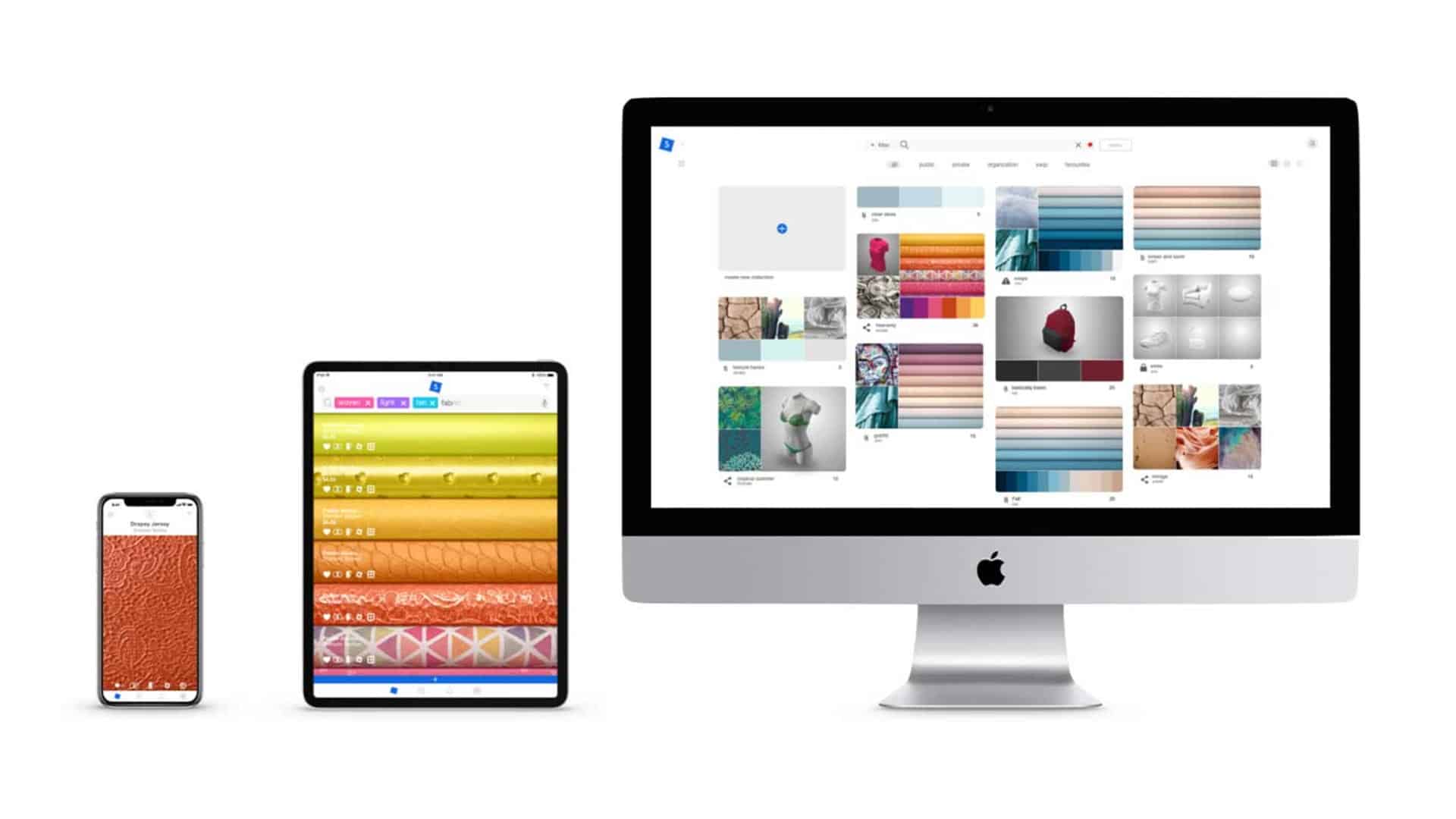

- In the production phase, we can browse through the libraries of materials and products of past collections, even those that haven’t made it to the market. Digital products “force” us to keep digital libraries organized; this, in turn, dramatically reduces the space required for inventory and makes it much easier to review past products when designing something new (or simply modernizing carry-over items).

Digital libraries like Dmix Cloud or Swatchbook, for instance, speed up the whole development process, giving designers a lot of flexibility in experimenting with materials.

We then move from these practical examples to more visionary — but nonetheless very real — ones, such as NFTs, which only exist in the digital realm (digital couture firm The Fabricant, for instance, deals with NFTs). We can own a piece of clothing that doesn’t belong to anyone else, but we don’t (can’t!) actually wear it.

“Iridescence”, a digital garment that sold for $9,500.

Linearity vs circularity

Developing a fashion product today means following a rather standardized procedure, which usually goes like this: concept definition, material and color study, product development (with prototypes), fitting. After a few models, the desired result enters production; and only then marketing picks up.

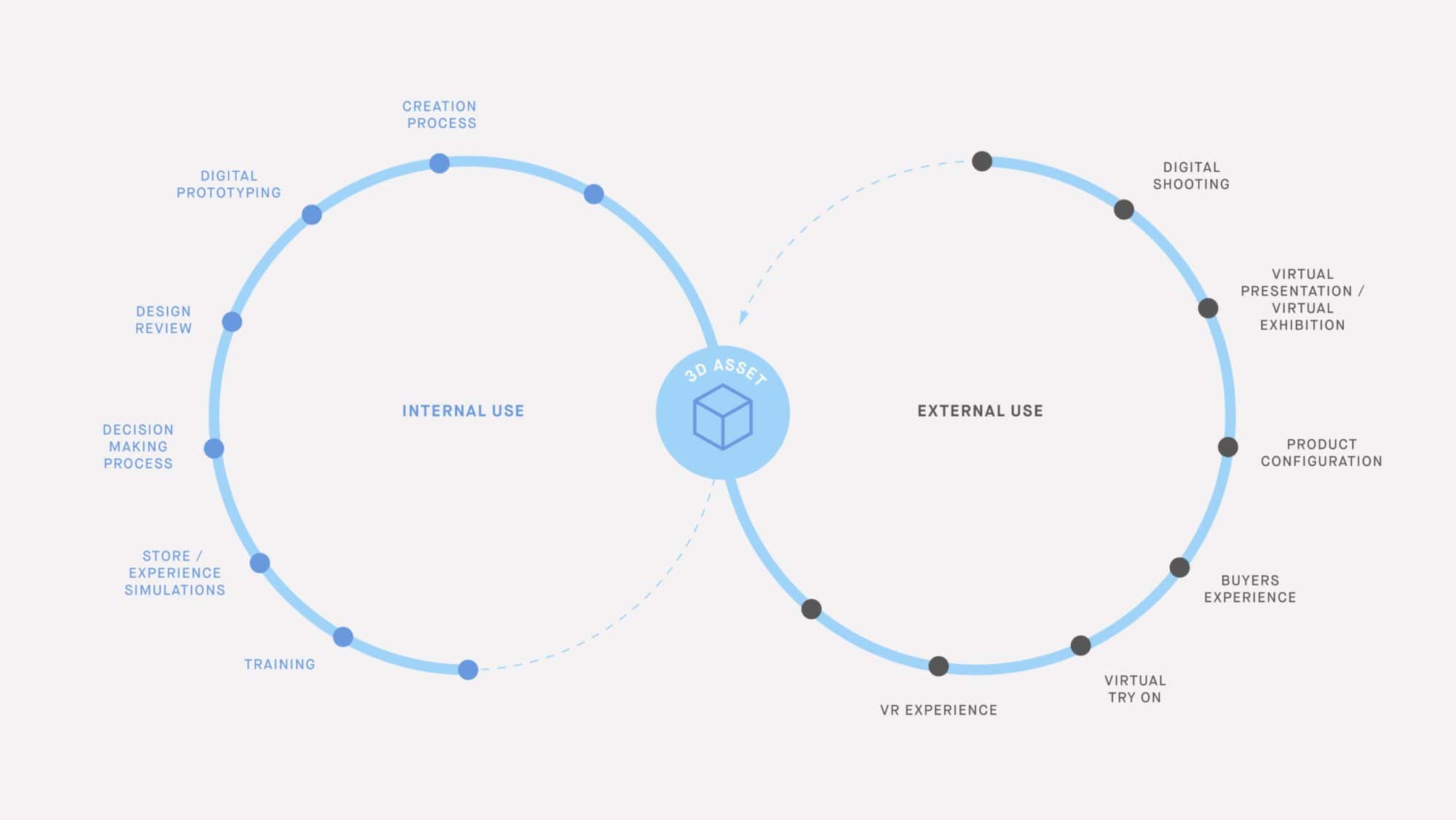

The digitization of a product changes this linear path, turning it into a more circular scheme.

Instead of following a model that essentially requires each step to be completed to move on to the following phase, the digital production begins with rapid prototyping and then moves on from then without a predetermined path. The object can be seen, modeled, changed, fitted, etc., whenever and however necessary.

Beyond that, as said, digital products make the life of the marketing department much easier, as the digital models can be used as a precise reference to create all the necessary material well before things actually go into production.

Physical prototypes simply make this impossible. Each variation becomes a project in and of itself, with all the accompanying costs. Each SKU (different color or material) requires its own prototype.

Let’s digitize everything then! — Hold up

The processes of dematerialization and digitization are expensive too. What is actually worth digitizing depends on what a company perceives as ‘valuable’; and to understand that, we need to look at the current production model. Where is the value? The product? Sales? Marketing?

For instance, if creating a single garment usually requires the development of three or four prototypes, then eliminating this very step can make the whole process worth it by itself. Production and development become cheaper and faster.

The same goes for companies that perhaps deal with multiple SKUs, whose digital versions can be shown to buyers and clients much more easily — no need for additional shootings. The value generated by digitization and dematerialization changes in accordance with numerous factors, each to be examined individually and per company.

Some firms have changed their approach as a first step toward a larger modernization process; some had already reached an advanced stage. IKEA in the world of furniture represents a well-known brand whose adoption of newer technologies was successful.

The IKEA configurator allows you to easily create different prototypes.

How to best approach this change?

The process is predictably complex, and necessitates that five key areas of a company be addressed before being approached. They are:

- Culture — Each firm approaching the path of digital transformation needs to start by looking at itself. It’s easy to talk about ‘digital everything’ when the average employee is 25; much less so when people twice that age run the place.

- Technologies — There are many different technologies, and it’s paramount that the right ones be selected. Fortunately, a lot of software is free and thus easy to experiment with.

- Skills — It is possible to ask for outside help at first, so as to see where and how 3D design makes a valuable contribution. Then it becomes mandatory to bring dedicated people on board, or reskill existing employees.

- Scale — Over the years, the process needs to scale up and become normal. If the team dedicated to digitization remains small, chances are the process won’t evolve beyond experimentation. Scaling things up also means taking advantage of the degree of automation software allows for.

- Exploration — The digital realm is constantly evolving, with new software, plug-ins, and case studies flowing in every single day. Companies willing to enter the digital world eventually need to explore, test, and prototype beyond (what becomes) the standardized production method.

So?

Digitizing and dematerializing products is a great opportunity to review and pare down the development process, but also a chance to evolve and upgrade certain organizational aspects of the company. It means giving birth to a new approach to work, and — most importantly — a new mindset. Does it make sense to digitize every product to make its development faster? No, most likely; however, it is paramount that firms reflect and understand the value a process of digitization can bring, so as to benefit the most from it. It is also important to start the process today, so as to avoid being unprepared when the next generational shift happens — or, indeed, the customers’ own mindset changes.